Warriors & Wounds

December 29, 1890 was a very cold day on the plains.

We visited on January 8. Got a feel for the biting wind through our coats and boots stepping out of the heat blasted van onto that meek and unassuming hill they call Čhaŋkpé Ópi– Wounded Knee.¹ It was 130 years and 10 days after the massacre.

Kelly Looking Horse, a Lakota Elder and historian, met us in front of the gates of the cemetery. He would teach us about what happened there, in 1890, in 1973 with the American Indian Movement standoff, the church that burned down, and other things since.

We learned about the mismatch. The U.S. Army 7th Cavalry armed with rifles and four Hotchkiss mini-cannons. This band of Lakota had been following Chief Big Foot. They’d decided they wanted to live the old way and follow the Buffalo herd across the plains. They’d been hunted down for resisting the reservation plan. The United States and their Army didn’t like resistance.

Shots fired.

Surrounded by men on horses, Big Foot’s people fled in chaos. It was a full band, including women and children, about 230 in total. Most were cut down by the organized bullets trained on their thípis and fires. Some made it to the stream and the valleys, but this only made them easier targets. At least 153 Lakota died, along with 25 U.S. soldiers. Twenty Medals of Honor were awarded to U.S. soldiers for their actions that day. Although the United States apologized for the incident in 1990, expressing “deep regret²”, the medals have not been rescinded. The Lakota were buried in mass graves.

How do you dig a grave in frozen ground?

The elksin baby booties were a heartbreaking reminder of the children killed at Wounded Knee, and all those Native children that go missing and murdered every year, still.

With all this in mind, some of us were unsure whether we should enter the grave area, which had a little silver fence around it. Kelly Looking Horse wanted us to. He wanted our prayers of penitence, of peace. He wants to heal this nation. He wants us to know and to remember.

One does not photograph ceremony. So this meaningful memory lives in our hearts, minds, and spirits alone. It belongs there.

Kelly was praying softly as we entered. We solemnly filed in a line facing the main memorial marker, a large gray stone. The fenced area was just long enough for all of us. Kelly beat a hand drum and prayed in Lakota. He told us that he was telling the ancestors that we came here with good hearts. He burned sage and gave us each a pinch of tobacco so that we could each offer it at the grave with our prayers. We did. The wind went still at that moment. Kelly told us this was a response of affirmation and a blessing.

Each of the ribbons is someone’s prayer.

Before we took some time to walk around in silent reflection, Kelly told us about Lost Bird. Lost Bird was a baby that had been found in her mother’s frozen arms after the massacre. She went on to be adopted by a General’s family, and brought up to be White and to forget her Lakota heritage. They named her “Zintkala Nuni³” or “Lost Bird.” She was abused. She didn’t fit in anywhere. She turned to sideshows and selling herself. Her husband gave her syphilis and she died on Valentine’s Day at age 30 in poverty. Buried in California, her body was moved to Wounded Knee to rest with her ancestors. Remember her and consider what might have been.

We were all humbled and heartbroken by Wounded Knee. Couldn’t put it into words. We’d read about it beforehand to prepare for our trip; but seeing it, being there, touching the graves, hearing the story from Kelly Looking Horse and praying with him there pierced the heart and soul.

We were all pretty quiet after that. We kept thinking about it, talking about it in our group discussions. The experience stayed with us.

We were all processing it differently, thinking different things. Days later I couldn’t get the thought out of my mind: were the soldiers my ancestors? I knew the right answer, that it didn’t really matter, specifically. I had been the recipient of the result of this conquest. I had to confront it whether these were my great uncles or not. But I still wanted to know. ‘Was one of them named Martin?’ I wondered if I could find a list of U.S. soldiers from Wounded Knee. I found a register of the enlisted on a historian’s blog⁴, a “Muster Roll.” I was shocked.

Not just Martin, James Martin. That’s my Dad’s name, and his Dad’s name. James is my middle name. We lived in Washington, D.C. He was the only Martin on the list and the only one I saw from D.C.

I guess I got what I was looking for. Proof that I couldn’t get away from this sickening heritage. Sure, I could change my name, my wife and I had already planned to. Not so much because of all this or out of shame, but because we wanted to envision something new together– “Everhope.” Nonetheless, the past was inescapable. I was living in its privileges. I needed to own up to what my people had done so I could live here today in these United States. If I sought honor in that living I needed to be honest and to seek rectification and reconciliation. I guess that’s part of why I came to Pine Ridge.

“Soldiers from Battery "E" of the 1st Artillery posed with three Hotchkiss artillery guns in front of Army tents in South Dakota, 1891. Hotchkiss guns were used in Army campaigns against Native peoples.”

—Native Voices, National Library of Medicine²

You in there, Jimmy, posing for the photographer?

Martin means “Mighty Warrior.” I’m the first man in my family, both sides, to have not served in the military. Goes way back. Dad’s side is from South Carolina, Mom’s from North Carolina. They both fought for the Confederacy. Who knows what they were doing before that.

My Dad pleaded with me not to join. He didn’t think it was worth it, and rathered I went to college. I followed his advice. I’m glad I did, but I think of my friends that went over to Iraq and Afghanistan, suffered the crisis of war and all its wounding inside and out to come back to cheery applause as “heroes.” Do they feel that way about themselves or do they feel used by a military system they didn’t understand? Youth in arms way.

I wondered about my legacy, my duty. I imagined that they were all noble causes. But they aren’t, really. Some of them are very ignoble. There are other ways to serve. Maybe I’ll be a military chaplain.

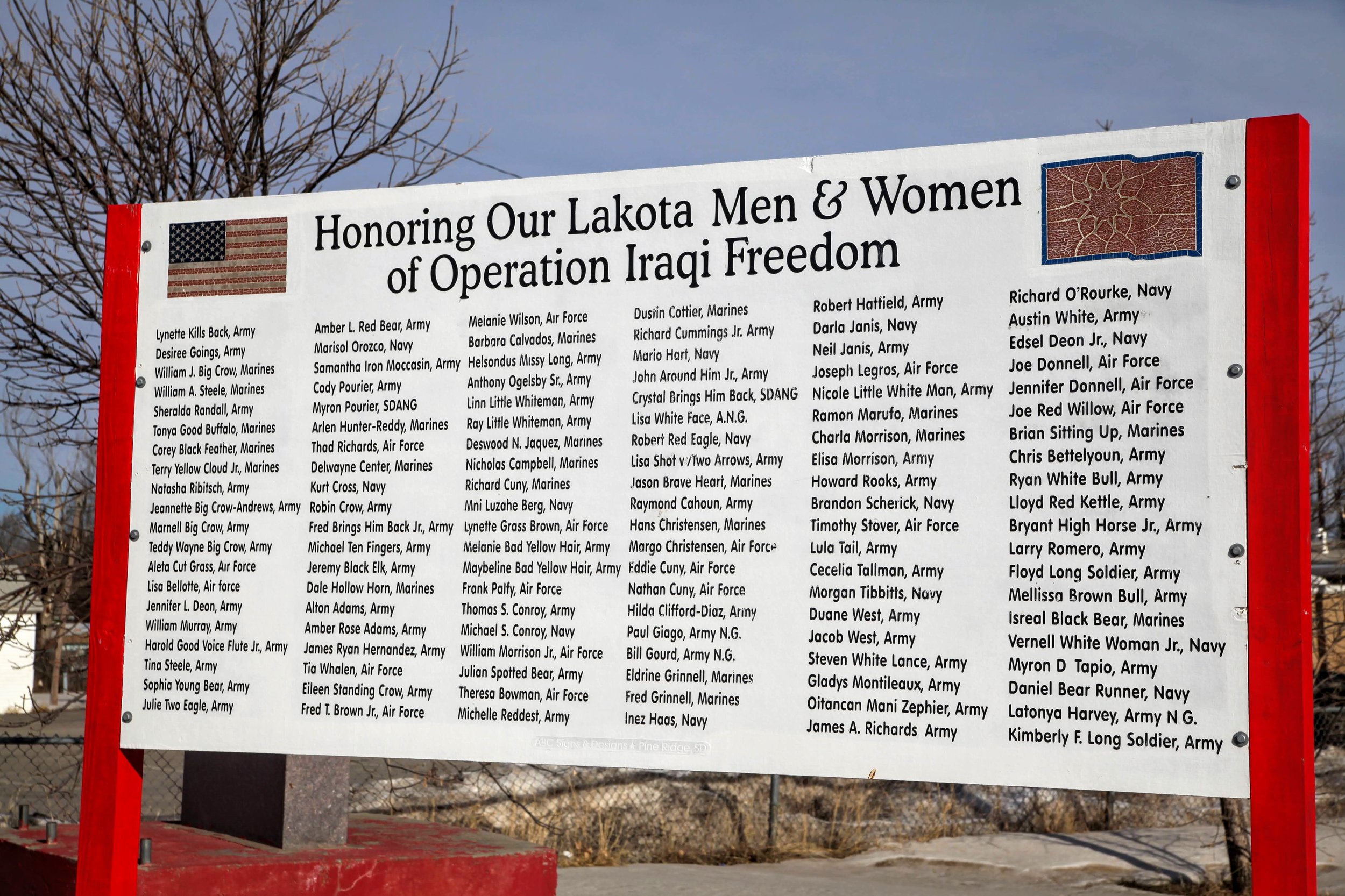

There are a lot of veterans’ memorials here.

Did you know that among all ethnicities, Native Americans have the highest rate of military service? I didn’t. That includes Whites.

I remembered how in seminary that year my Hebrew Bible class was interpreting Joshua. We read Robert Allen Warrior’s take that when American Indians read Joshua they identify with the Canaanites. That is, they identify with the “bad guys” who are patriotically murdered by the lot– men, women, and children– entire cities razed for the glory of the Israelites. This land was God-given, saith the good book… and it would be taken in blood.

Jeez. What kind of faith is this?

As a kid I was taught how great this was, had a close friend at church named Joshua. He became an Army Ranger. Still in.

In all this, what has been left unseen, unsaid? Wounded Knee was horrific, bloody and needless. Most people know about the Trail of Tears, too. But what about all the other countless specifics? Not just the incidents of abject violence but the methods of dehumanization, genocide, and takeover. How many more Lost Birds were out there?

What about the wound on Tȟuŋkášila Šákpe?

It means “Six Grandfathers.” It was a sacred mountain in the sacred Black

Hills from which the Lakota believe they originated.

Perhaps you know it by another name: Mount Rushmore.

These are the Fathers of our Nation, the United States. Now I was seeing them through different eyes with Native stories in my heart. Lakota voices say it better than I can.

What South Dakota and the National Park Service call ‘a shrine to democracy’ is actually an international symbol of white supremacy.

-Nick Tilsen, Oglala Lakota, NDN Collective⁶

To me, they are still great men, as in, they achieved great things and led with visions of a better world in their respective eras of U.S. history (am I just telling myself that?) But what’s also true is that they were all White-supremacist, wealthy, landowning men, who oversaw militaries and the conquest of Indigenous Peoples. Two of them owned slaves. Lincoln freed the slaves but he also hung the Dakota 38, who, starving from forced exile, fought the boys in blue after we broke another treaty. “Better world,” I said. Can I be sure? Perspective is everything. Be careful what you put into stone, and where.

By the way, what about the Mothers of our Nation?

The apologetic construction taking place during my visit made this photo too easy.

Mount Rushmore is a most bold desecration of nature and a Lakota religion in harmony with it, for the construction of a new, egotistical civil religion. Against the protests of local Lakota leaders, White politicians still blow up fireworks there on the Fourth of July.

O beautiful for pilgrim feet

Whose stern impassioned stress,

A thoroughfare for freedom beat

Across the wilderness!

America! America!

God shed His grace on thee,

Till paths be wrought through wilds of thought

By pilgrims foot and knee!⁷

Grace shed how?

Wounded Knee Hill

Ravine near Wounded Knee Creek, possible location of massacre

-

¹ Military Wiki. “List of Medal of Honor recipients for the Wounded Knee Massacre.” Fandom.com. Accessed May 3, 2022.

https://military-history.fandom.com/wiki/List_of_Medal_of_Honor_recipients_for_the_Wounded_Knee_Massacre² U.S. National Library of Medicine. “1890: U.S. Cavalry massacres Lakota at Wounded Knee.” Native Voices - Native Peoples’

Concepts of Health and Illness. Accessed May 3, 2022. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/nativevoices/timeline/377.html³ South Dakota Public Television. “Lost Bird of Wounded Knee.” Accessed May 3, 2022. http://sdpb.sd.gov/Lostbird/summary.asp

⁴ Russell, Sam. “D Troop, 7th Cavalry Regiment Muster Roll.” Army at Wounded Knee. Feb. 2, 2014.

https://armyatwoundedknee.com/2014/02/02/d-troop-7th-cavalry-regiment-muster-roll/⁵ Warrior, Robert Allen. “A Native American Perspective: Canaanites, Cowboys, and Indians.” In Voices from the Margin:

Interpreting the Bible in the Third World, edited by R.S. Sugirtharajah, 287-295. Maryknoll (New York): Orbis Books, 2016.⁶ Estes, Nick. “The Battle for the Black Hills.” High Country News. Jan. 1, 2021.

https://www.hcn.org/issues/53.1/indigenous-affairs-social-justice-the-battle-for-the-black-hills⁷ Bates, Katherine Lee. “America the Beautiful.” The Congregationalist. July 4, 1895.

https://www.purpleheart.org/static/forms/AmericaTheBeautiful.pdf