Wakaneja / Sacred Beings

Photo by Kathi Matthews-Risley

During children’s time in the basement of the old Presbyterian church the three little girls would sit me down in front of the toy kitchen and “cook” me meals, rotating the various palm sized plastic burgers, steaks, eggs, and pizza available to them. I played along, tried to be a grateful guest, to eat my food and enjoy it, sitting in the tiny chair.

I thought of how this was good preparation for me, that I would be playing like this with my son soon, being imaginative and learning social dynamics. I hadn’t been around all that many kids since I left my little sister to go to college.

Then between her shrill laughs and pronouncements of meals being cooked and ready, Kisha (name changed) said something that broke my heart. “Be careful or you’re gonna snatch me, take me away.” She said it a few times, kind of laughing but in a dark way. I imagine she was repeating warnings she’d been given, warnings about men like me. White guys that come in, seem nice, play along, and wait for their moment to steal innocence, to take advantage.

My reaction was to ignore her, pretend like I didn’t hear or didn’t understand. I am a nice guy, really. But assurances were cheap, and wouldn’t protect her from real danger I couldn’t see either. It was sad to me that she had been taught this, but maybe it was necessary vigilance. The Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Children are countless, it’s a terrifying reality. Just another thing I’d read about, but really, knew nothing about.

Wakaneja is the Lakota word for children. It means ‘sacred beings.’

Let the little children come to me, and do not hinder them, for the kingdom of heaven belongs to such as these.

-Jesus, Matthew 19:14

What if we took that seriously? What if we treated children as the listeners closest to the voice of the Master, not as those who need to be perpetually taught by us? How might they teach us in their openness and innocence? What have we forgotten that they still carry freely?

Basil Brave Heart is an Elder that came and talked to us on my birthday. Basil talked about a lot of things. He told us about being taken away from his parents, having his hair shaved, being forbidden to speak Lakota, and being taught to be Catholic and to hate his Nativity.

Basil told us how he could hear some of the boys being sexually assaulted by the priests at night.

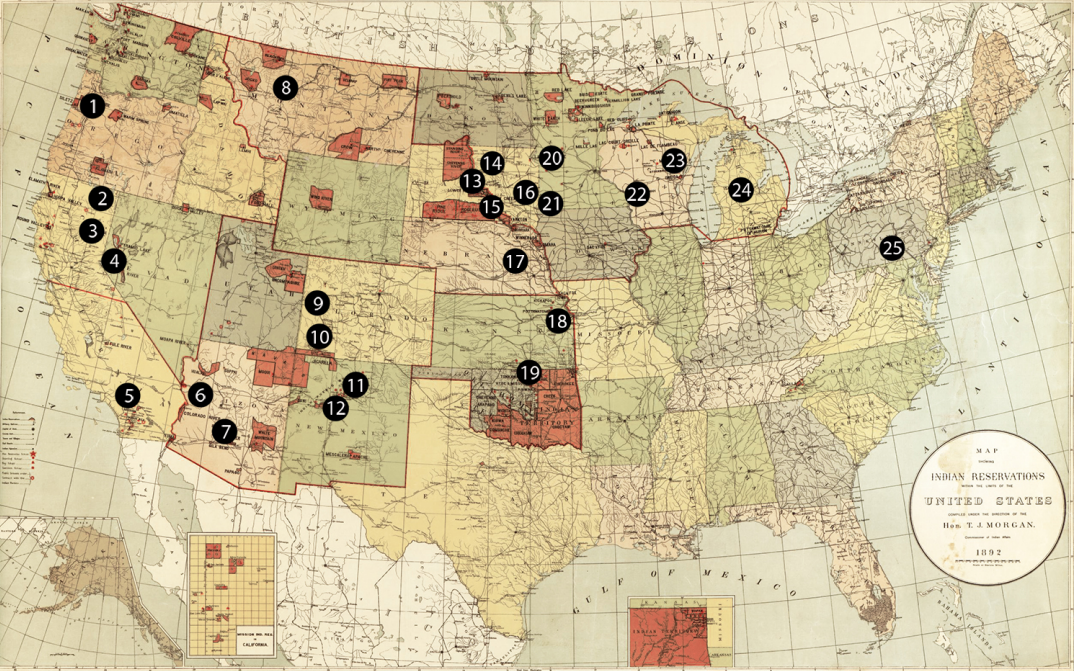

What is most heartbreaking is that this was not a special or irregular instance. This was the common experience at every Indian School across North America, part of Indian Wars Army veteran Captain Richard Henry Pratt’s vision to “Kill the Indian, Save the Man.”¹

Library of Congress, United States Office of Indian Affairs

Aside from the cultural genocide that left several generations of American Indian children with a fractured relationship to their ancestry and identity, many children died. They’ve begun to find the mass graves where the schools used to be.

Basil made it out, traumatized but alive. Still a teenager, he found himself in the U.S. Marines, another strict regimen requiring obedience to a alien system. He had rage and sought self-esteem, he wanted to prove himself as a warrior. Soon he was headed for Korea. Put on the frontlines, he saw a lot of men die. It was a chaotic bloodbath. When he came back he turned to alcohol to numb his pain.

But Basil remembered the teachings of the elders in his life, his Tiyóspaye², the wisdom of his relatives in the Spirit World who guided him to the light, to healing.

The organizers of our trip were fond if stark juxtaposition. At no time was this more severe for the group than on January 13. We had lunch after Basil’s talk, then we drove down the road for a tour of Red Cloud Indian School where Basil had been boarded.

The school is named after Mahpíya Lúta, Chief Red Cloud.³ His grave is just behind the school, up the hill. He had resisted U.S. forces successfully in Montana, but recognizing the relentlessness of the pioneers’ expansion, he relented to pressure and accepted the reservation system where he felt he and his people could be safe. They moved to Pine Ridge and soon after began working with Jesuit missionaries to found a school “so that our children may be as wise as the white man’s children.” He didn’t know that the teachers would try to replace Lakota culture with White Catholic culture, and that they would abuse and shame the children. This is not mentioned on the school’s “History” webpage.⁴

Did he ask for that cross on top, or did some one else put it on there?

The school is very different now. Having recognized the destructiveness its past, the current administrators of Red Cloud, mostly Lakota, teach the language from a young age, embrace the beauty of Lakota culture, and encourage the students creativity. There is a well respected arts center and gallery on campus.

Stained glass throughout the church at the center of the campus is done in Lakota style patterns and there is local art hanging on its walls. Instead of a confession booth there is a room marked “Reconciliation.” Jesuit initiates still come here for their training, but they take a position of listening more than telling. Openness not dominion.

Basil Brave Heart and Red Cloud Indian School embody testaments to healing.

Could they have done it without the guidance of the Tiyóspaye / ancestors and the movement of Wakȟáŋ Tȟáŋka / Great Spirit? They would say no, I agree, and I bet Father Joe would, too.

Now, at Our Lady of the Sioux Catholic Church down the road from Red Cloud, they speak Lakota in the service and write it on the altar, fly a hand painted banner of Algonquin–Mohawk Saint Kateri Tekakwitha, and hang the four sacred colors from the rafters.

Christ is not the enemy of these people, or their faith. The Church had been, sometimes it still is, but it doesn’t have to be that way. These places reminded me that even if faith and mission had been toxic in the past, it can change, it can become beloved community.

Red Cloud Indian School, original building; now The Heritage Center

And yet nothing is perfect. Some people don’t want to forgive and still reject the bitter taste of Christianity’s wounds. I can’t blame them. Kid’s still scratch their names into the school walls, which carry those wounds. With that neutered tree out front and the looming icon statues abiding in an ongoing abuse scandal, the Church would rather ignore than confess; I still felt a little uneasy.

The basketball rivalry with the public school across town is pretty fierce.

At that school, Pine Ridge High, Will Peters teaches Lakota history and culture and started Waziahanhan Siyotanka Okolakiciye, Pine Ridge Flute Society, to teach the kids how to play the traditional flute. He told us his story, how the kids love it and connect to it, how meaningful it is to them and to him.

I fell in love with playing the flute, it can help you heal, to be calm and I wanted to share that with my students.

-Will Peters, teacher⁵

For me, playing the flute is an easy way to express myself, gives you a voice.

-Joel Thunder Hawk, student

Pine Ridge Flute Society recorded a 20 track album, which went on to receive the 2018 Native American Music Award for Flutist of the Year.

Where we come from, a lot of people are struggling, and when we created the Flute Society, we were dealing with suicide ideations in our schools across the reservation. So playing the flute brought us all together as a community and an extended family to create this music so that people can have something to escape to and our homeland can be proud.

-Jayden Peters, excerpt from acceptance speech, Will’s grandson⁶

Pine Ridge Flute Society CD, 2018

What would I teach Nathan? To whom would I entrust his care? Can I do this?

On our last full day at Pine Ridge we visited another Red Cloud. Henry Red Cloud is the fifth generation descendant of Chief Red Cloud⁷, now a Chief himself. Trained as an engineer, he wants to empower Native communities across Turtle Island (North America) by providing affordable, DIY renewable energy solutions. Red Cloud Renewable Energy was born, and has been recognized nationwide.

Chief Henry recognizes the responsibility he has to the sacredness of creation and to the future, especially in light of the climate crisis, which will affect us all. He wants to make sure he does what he can to respond to this crisis and teach others how to do so in practical ways. We were all very impressed and grateful for his taking the time with us.

We all descended from someone. Others will come after us, even if we don’t have children ourselves. Our actions matter.

Children are sacred and they are potential. What an incredible responsibility to care for them! What a blessing my son Nathan is!

Tell the children the truth. Give them love and teach them to love. To love the Creator and all Creation. Heal America. Heal the world.

Elkskin booties by Teresa Red Feather, worn by my son Nathan, held by his mother Emily on Mother’s Day, 2020

-

¹ National Park Service. “The Carlisle Indian Industrial School: Assimilation with Education after the

Indian Wars (Teaching with Historic Places).” April 28, 2020.

https://www.nps.gov/articles/the-carlisle-indian-industrial-school-assimilation-with-education-after-the-indian-wars-teaching-with-historic-places.htm² Akta Lakota Museum & Cultural Center. “Tiyóspaye - The Extended Family.” Accessed May 7, 2022.

http://aktalakota.stjo.org/site/News2?page=NewsArticle&id=8670³ Biography. “Red Cloud.” Oct. 27, 2014. https://www.biography.com/political-figure/red-cloud

⁴ Red Cloud Indian School. “History.” Accessed May 10, 2022.

https://www.redcloudschool.org/page.aspx?pid=429⁵ Crash, Tom. “Pine Ridge Flute Society Releases First Album” Lakota Times. Aug. 3, 2017.

https://www.lakotatimes.com/articles/pine-ridge-flute-society-releases-first-album/⁶ World Music Central. “Winners of the 2018 Native American Music Awards Announced.” Oct. 18, 2018.

https://worldmusiccentral.org/2018/10/18/winners-of-the-2018-native-american-music-awards-announced/⁷ Lakota Solar Enterprises. “Henry Red Cloud.” Accessed May 8, 2022.

https://www.lakotasolarenterprises.org/henry-red-cloud